Chapter Four - The Great Armadas Came

AFTER ATTACKING our shipping in the Channel and coastal installations during the summer of 1940, enemy aircraft moved inland. To begin with, activity around Ferryden was limited to the odd reconnaissance flight or 'hit and run' raid, but in August this increased, with heavy attacks on local R.A.F. Stations. The first of these involved dive bombers at an airfield located several miles east of the village. Severe damage was caused to buildings, and many planes were destroyed on the ground.

I saw one very large explosion which resulted in a huge mushroom cloud and showers of incandescent metal cascading in all directions. A pall of smoke hung over the station for some time, and we learned that there had been casualties, with a number of service personnel killed. Two other airfields in the area were heavily bombed on a number of occasions, resulting in loss of life, the destruction of aircraft on the ground, and severe damage to buildings. Every evening we listened with some trepidation to the news bulletins. These confirmed that attacks were widespread throughout the South East, and we realised that a crucial phase in the conflict had been reached. It was 'The Battle of Britain'.

The defensive system set up to counter the German onslaught consisted of a chain of radar stations to locate and 'pin point' the enemy formations, anti-aircraft guns in depth along the coast, a fighter zone which covered a wide area embracing many towns and villages in the South East, including Ferryden, and a final 'wall' of barrage balloons around-London. The radar stations gave the fighters advanced warning and directions to ensure that they were airborne and in a position to intercept the raiders before they reached their targets.

The German strategy was, quite simply, command of the air, to be followed up with a full scale invasion. Initially they concentrated their attacks on the radar stations and air fields In the South, and although we were heartened by the apparent success of the R.A.F., the losses they suffered were grievous and could not be sustained. However, as so often happens in these situations fate stepped in. The accidental off-loading of bombs on London from a plane that had lost its way resulted in a 'retaliatory' bombing of Berlin. This so infuriated Hitler that he changed the emphasis, and mounted full scale attacks on London. The change took pressure off of our hard pressed defences, and turned the tide of battle in our favour.

Initially, the enemy aircraft were operating at great heights, or attacking targets at some distance from the village. This left us in an enviable position. We were able to take advantage of the summer weather, and observe the fighting without much danger to ourselves. That situation could not continue, and the 'chickens came home to roost' one Saturday evening. We had just finished one of Mother's special 'High Teas' when the air raid warning sounded. By this time, warnings were such a regular occurrence that nobody took much notice of then. George had arranged to go to a cinema in the nearby town and was waiting for a bus in the High Street. Mother was doing the washing up. Father was picking a few flowers In the back garden, and I was in my bedroom.

Suddenly, there was a tremendous clatter from the direction of the High Street and a Spitfire roared past my bedroom window at very high speed, with a Messerschmitt Me 109 in hot pursuit. The planes were very low and banking to an angle which gave me a clear view of the pilots. In spite of having an enemy fighter on its tail, the Spitfire did not appear to be damaged, but the Messerschmitt had one side completely smashed in. The clatter we heard just before the two planes came into view was a burst of machine gun fire. Later on, we learned that both of the combatants had run out of ammunition, and that the German plane, being short of fuel, had landed in a field several miles away.

George was particularly interested in this incident, as he had a 'grandstand view.' He was almost directly under the planes as they used the last of their ammunition. Both pilots must have realised what the position was, because they flew alongside one another for some time and communicated by the use of sign language. This must have been effective, as the German pilot was somehow persuaded to land. He climbed out of his plane and was taken prisoner. After circling the spot to see that everything was alright, the Spitfire pilot threw out a packet of cigarettes in acknowledgement.

This incident was an example of the more 'gentlemanly' behaviour which prevailed among the majority of fliers at that time, contrasting sharply with the attitude of some German fanatics at a later stage in the battle. They deliberately machine gunned defenceless R.A.F. pilots who were escaping from their stricken aircraft by parachute.

Later on that same evening, I observed two fighter planes following one another in what seemed to be an orderly procession. Suddenly there was a burst of machine gun fire and the leading aircraft, an Me 109, broke in two, the tail spinning into a corn field and the rest crashing on the edge of a nearby wood. Fortunately, the pilot escaped by parachute and was taken prisoner.

Although by previous standards this was a very eventful day, it was just a foretaste of things to come. From this point on the battle got more intense, with increasing numbers of enemy aircraft taking advantage of the glorious summer weather. No doubt the enemy had good reason to think that things would go the way of his other conquests, but he grossly underestimated the strength of our resolve, the spirit of the civilian population, and the courage of those wonderful young men who fought and died over Southern England.

There can be little doubt that the weather had a profound effect on the level of activity, with enemy planes above us in clear blue skies almost every day. The attacks were so frequent that we tended to ignore them. It was not uncommon to be bombarded in the street with empty bullet cases ejected from our own fighters, or to hear the 'zing' of shell splinters as they clattered onto corrugated iron sheds or bounced off roof tops into the garden.

We had a great time souvenir hunting and competed with one another to see who could collect the most memorabilia. These ranged from shell splinters to bits of aircraft. One of the most prized possessions was aluminium fuel piping, which could be made into decorative rings. These were much sought after, and often sold in aid of charity or the war effort.

The battle raged above us, and day by day the heavens were decorated with contrails from fighters and the great bomber fleets which darkened the skies as they sped on journeys of destruction towards the capital. Aircraft engines whined and roared as the pilots pushed them to their limits, twisting and turning in desperate attempts to destroy an enemy or escape from his clutches. Every now and then, we heard the sickening scream of an aircraft gyrating earthwards in Its final plunge, and saw parachutes bobbing on white puffs of cloud like jellyfish in a windswept sea.

We were becoming complacent. Momentous events were taking place all around us, and we were going about our business as though nothing had happened. 'Complacency' was hardly the word to describe Father's devotion to his allotment garden during the war, or my interest in it. Sunday was still a 'day of rest', and we made the most of it. It was just another of those lovely Sunday mornings when he and I went to harvest some of the fruit and vegetables he had so lovingly tended earlier in the year.

As usual the day started with a shroud of mist in meadows adjacent to the river, but the hot sun had quickly burned this off and built up a heat haze. By eleven o'clock the air was still, with a mirage effect clearly visible on the tarmacked road surfaces. This shimmered and distorted objects in the distance, making them look as though they were floating on a pool of water. There were no vehicles to disturb the peace or pollute the atmosphere, and the silence was complete except for the noise of insects, the song of the skylarks and chatter of birds in-the hedgerows squabbling over a morsel of food or some disputed territory.

Father carried out his usual inspection of the garden, and picked a few flowers for Mother. He collected an armful of beans, and dug a few potatoes for lunch. The flowers he tied to the handlebars of his bicycle, and secured the vegetables on a carrier over the rear mudguard. He then harvested the remaining onions, and hung them up in the shed to dry. I helped by picking a basket of soft fruit, and hauled up a few buckets of water from the nearby ballast pit to top up his water butts. It was tedious work but the morning was extremely pleasant and we enjoyed it.

We finished working on the garden at twelve-thirty, and it was time to go home for lunch. We collected the tools, put them in the shed, and got ready to leave. Normally, Father would go home on his bicycle and I would I walk, but at that moment the air raid warning sounded. "Come on mate" he said, "You sit on the crossbar. I don't like the idea of you walking home alone when there's a raid on," It was a bumpy ride, but we made it to the allotment gates without incident and set off along the tarmac road towards the village.

We had covered about half the distance when I heard the unmistakable throb of diesel aircraft engines coming towards us from the East, and we both knew what that meant. Father glanced anxiously over his shoulder, and increased his speed. The throb of the engines grew more intense, and as we got to the outskirts of the village we dismounted and turned to see what was happening. The scene made us gasp in astonishment. There were so many planes, it looked as though the horizon had changed to a black mass and was about to lift up. As this 'Great Armada' drew nearer, we could see that it consisted of huge bomber formations, flanked by fighters on either side and a screen above for extra protection.

It was a magnificent sight. The planes, in perfect formation and symmetry, were like Teutonic Knights of the sky. Rays from the sun reflecting on the windscreens made them flash and glitter as though they were crystal chandeliers, and the wings and fuselages gleamed as if they had been honed and polished the night before. The throb of the engines intensified into a mighty roar as they passed overhead. The spectacle could so easily have been mistaken for a film sequence from 'The Shape of Things to Come'.

The power they represented was awesome, and at the time it seemed as though our defences had been mesmerised into submission. There were no puffs of smoke from exploding anti-aircraft shells, and no sign of our interceptors. We stood and watched with wonder and amazement as this great aerial fleet, in all its splendour, flew relentlessly on.

For a minute or two we continued to watch, rooted to the spot as if we were in a hypnotic trance, when suddenly the heavens erupted. From an orderly, disciplined spectacle of military might which seemed to mock our will to resist, the enemy formations disintegrated. Just how it happened I will never know, but the skies turned from order into chaos in a matter of seconds. Planes appeared to be flying aimlessly in all directions. The noise of the aircraft was overshadowed by the clatter of machine guns and cannons. The crump of bombs exploding is the distance was interspersed with the whining and screaming of engines as the adversaries twisted and turned, or climbed and dived, in mortal combat. It was a nightmare that had suddenly become reality.

We hurried home to find Mother in the garden in a state of great distress. "Those poor boys" she sobbed, "what will become of them?" She repeated this over and over again, and would not be comforted. The war was no longer a news bulletin on the radio, or a noise in the distance. It had come to disrupt our lives, as it had for so many in the war-torn countries of Europe.

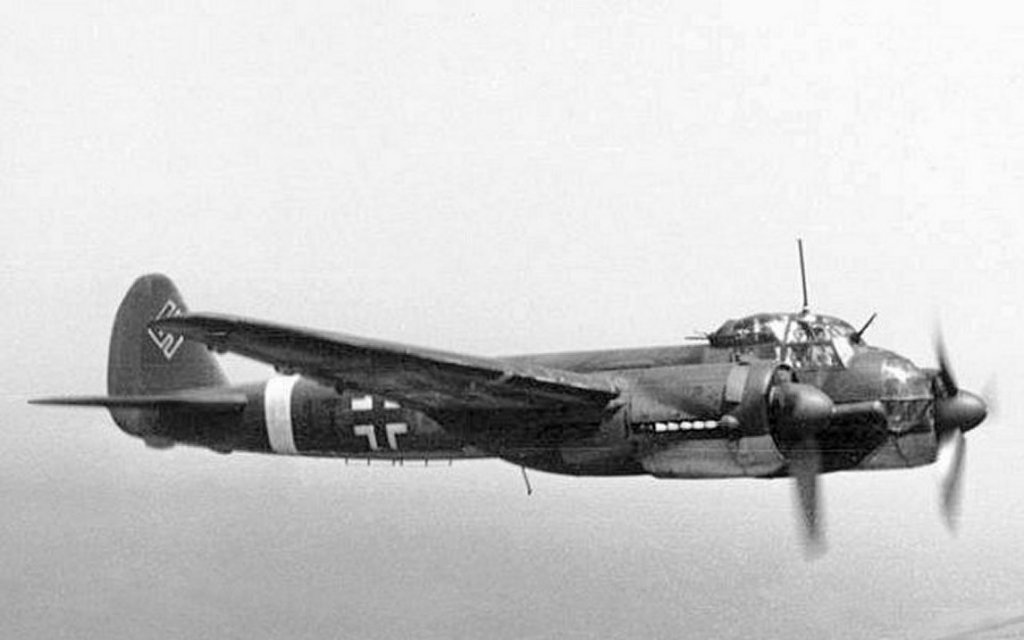

Father took her inside, and as he did so, a twin-engined plane came in low towards us. At first, it seemed to be making a pass over the village, but as it drew closer I could see that it was damaged, with flames streaming from holes in the fuselage. The engines were still running, and just before it flew over, two of the crew jumped to safety, their parachutes ballooning out behind them. At that point the aircraft seemed to falter, the nose went up slightly and it turned very slowly onto its side.

I must have run from the back of the house to the front in less than two seconds. Time enough to see the stricken plane plunge earthwards, flames and smoke now enveloping the crosses and Swastika on its sides and tail. It disappeared behind a clump of trees and exploded. A huge pall of flame and smoke shot skywards. The explosion was violent, shaking the ground and rattling windows and doors throughout the village. Witnesses looked on in awe. "Dear Lord, the church has gone" cried one old lady, as the pall of smoke climbed higher and higher. It looked as though she might be right, and I ran off to investigate.

The plane, a Ju 88 bomber, had crashed Into an orchard several hundred yards from the church and was burning fiercely. I approached the crash site, and it was clear that its cargo of bombs had exploded on impact. The machine had been blown to bits, together with the pilot, who did not escape with the crew. The scene was horrific, with charred and clearly identifiable human remains being scattered over a wide area.

As the military had not yet arrived, I walked into the orchard to get a closer view of the crash site, and almost trod on one of the pilot's limbs. This sent a shudder down my spine, and I retreated uneasily to a more respectful distance. A guard was soon mounted, and the public were not allowed to get too close - partly because of the obvious dangers from any unexploded bombs, and partly because of the need to respect the remains of a very courageous airman. Both George and I were convinced that he sacrificed his own life to save his comrades and to prevent the plane crashing onto the village.

Meanwhile, a Spitfire spent some time undertaking a series of acrobatic manoeuvres or 'victory rolls' over the smouldering wreckage. This was a common occurrence during the war, although it might be viewed as rather callous in today's political climate. We did not see it that way, and no disrespect was intended towards the man who had lost his life. At that time we were alone, and facing an arrogant and ruthless enemy who cared little for the sufferings inflicted on his unfortunate victims. We felt there was every reason to make our feelings known, and this was a gesture of defiance.

One of the crew members who survived the crash was taken prisoner by the Home Guard. He landed in a field just outside the village, and his descent had been watched by a young recruit and an old soldier who had served in the 1914-18 war. The young man, armed with a rifle, jumped a fence and ran towards the airman threatening to shoot him. The older man, seeing his anger, ran after him and grabbed his rifle. "We'll have none of that," he said, "the war's over for that young man".

The German surrendered and was taken to a nearby house, where the lady owner gave him tea and biscuits while the 'Guardsman' telephoned for an escort. The escort came and the prisoner was taken by car into custody. As he passed through the village a crowd gathered, and there was considerable hostility. Some people were shaking their fists and hurling abuse, others were even more threatening. The situation was getting out of hand when an elderly lady rebuked them. "Leave him alone," she said "he's some poor mother's son." From that moment tempers cooled, and the car was allowed to proceed on Its journey.

Although this air raid was probably one of the most dramatic daylight actions over Ferryden, the battle continued, with fleets of aircraft passing overhead on an almost daily basis. We listened to the radio every evening, eager to know how many enemy aircraft had been shot down, and how many of ours had been lost. It was almost like a cricket scoreboard. Day by day the numbers mounted, and it was clear that we were gaining the 'upper hand'.

The advantage of fighting over our own territory meant that a large number of our pilots escaped from their burning planes and were able to rejoin the battle, whereas the German airmen were taken prisoner and took no further part in the war. However, there were still far too many of our brave young men who did not make it, and I can recall one such occasion when a Spitfire was shot down by an Me 109 when on patrol over the village.

It was a weekday afternoon, and school lessons had finished for the day. The air raid warning had been in operation for some time, and I was walking across the fields with one of my school friends, Fred Peers, looking for mushrooms. Suddenly, there was the unmistakable 'pom-pom' sound of cannon fire immediately above us, and two fighter planes came into view. With utter dismay we realised that one of our airmen was in trouble. The planes flitted from cloud bank to cloud bank but there was no escape, and one final burst of fire sent the Spitfire into a spin, smoke streaming from the engine.

Initially, the engagement had taken place at a great height, the aircraft being little more than specks in the sky, but as the Spitfire plunged earthwards it grew larger and larger, and we realised that it was coming straight for us. Instinctively, we took cover under a nearby hedge and murmured 'The Lord's Prayer' for comfort, but as the scream of the engine became more menacing, we panicked and ran into the open.

Whether or not the pilot was conscious and saw us we shall never know, but at that moment he levelled out, skimmed the hedge, climbed over some trees on the other side of the river, and 'belly landed' in a field. The plane travelled some distance, ploughing up the ground as he went, but tragically it hit a massive wooden fence and burst into flames. Valiant rescue attempts were made by people living nearby, but the heat and exploding ammunition made this impossible. Fred Peers and I got to the scene of the crash a few minutes later, but by this time the plane was a mass of flames and the pilot had perished.

This incident was one of the last of the daylight raids over the village. The German air force had suffered such heavy losses during the onslaught that they decided to call the whole thing off. The threat of immediate invasion was over and, we had won our first significant victory. The 'Battle of Britain' had ended, but Ferryden had to endure a great deal more in the years to come.

This period of the war had forced us all to take a long hard look at ourselves. Our sense of values and attitudes had changed. We had lost a lot of our earlier complacency and moved from a position of gloom at Dunkirk to a belief in ultimate victory. We were united in our determination to defeat Nazi Germany. All the old enmities and family feuds were forgotten. People who would not have been seen dead with one another before the war worked together, helped each other, and in some cases lived together. Politics and class divisions, so often a 'bone of contention', were forgotten. The one uniting factor was the war and the cause for which we were fighting - nothing else mattered.